The annual index, which is part of a broader Economist Group effort for International Women’s Day, suggests progress to the top of companies is slow for women in most OECD countries.

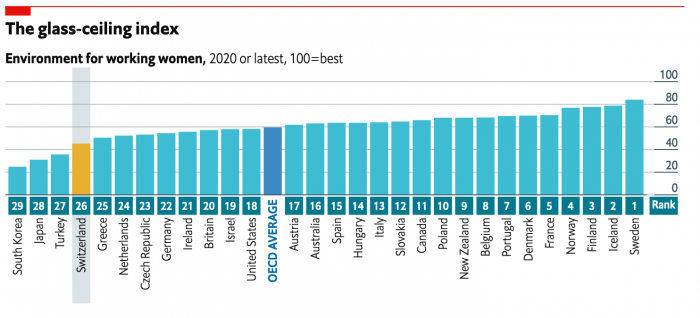

The Economist’s Glass Ceiling Index (GCI) shows that women are still lagging behind their male counterparts in senior positions, making up on average only a third of managers across the OECD. The GCI is a yearly assessment of where women have the best and worst chances of equal treatment at work in countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a group of mostly rich countries.

The GCI, which combines data on higher education, labour-force participation, pay, childcare costs, maternity and paternity rights, business-school applications and representation in senior jobs to create a ranking of 29 OECD countries, shows that Sweden is the best place to work if you are a woman, followed by its Nordic neighbours, Iceland, Finland and Norway. The Nordics are particularly good at helping women complete university, secure a job, access senior positions, and take advantage of quality parental-leave systems and flexible work schedules.

Switzerland, in a group with South Korea, Japan and Turkey, bottoms out the index for the ninth year in a row (before Turkey joined the index, we’ve actually been third to last). While Switzerland is doing slightly better than the OECD average on women’s participation in the workforce, women in managerial positions, company boards, and parliament, the situation looks bleak on several other parameters.

There’s the childcare cost, for which Swiss parents need to set aside by far the highest share of their average wage compared to all other OECD countries. There is the comparatively weak support of new mothers, who only receive the full-rate equivalent of 8 weeks paid maternity leave compared to, for example, 49 weeks in neighbouring Austria and 42 weeks in Germany. Our neighbours also happen to have comparatively generous paternity leave in place. In Switzerland, in contrast, this year’s index still reflects the non-existent paid leave for new fathers. On this one, there’s hope on the horizon, and we should start seeing improvements already next year as the Swiss paternity leave has come into force on 1 January 2021, following last year’s vote on the issue. Whether this will influence the still quite hefty pay gap (women in Switzerland currently earn about 15% less than men) remains to be seen.

Additional highlights of The Economist’s 2021 glass-ceiling index:

- The US moved four spots up on the index from last year. While its proportion of women in management roles and on boards is above average, it remains stuck below the OECD average with no federally-mandated paid parental leave

- Britain improved by three spots on the index this year; its share of women in senior jobs is around a third

- Germany moved down the ranking from last year to #22. German women hold just 29% of managerial roles, and a quarter of seats on boards

- France ranks #5 in the GCI, the same as last year. France ranks second for the highest share of women on company boards, behind Iceland

This is the ninth year that The Economist has released its glass-ceiling index. When it was launched in 2013, there were five indicators and 26 countries; today, it consists of ten indicators, including maternity and paternity leave for 29 OECD countries.

The Glass Ceiling Index sits within a new hub, « Women Around the World« , The Economist has launched in celebration of International Women’s Day. Sitting in front of the paywall, it highlights some of the best coverage across The Economist on the lives of women around the world—from inspiring stories to the political and economic inequalities that persist globally.

To view the full interactive glass-ceiling index, please visit The Economist’s hub with content on International Women’s Day: https://www.economist.com/IWDay

Soure: The Economist