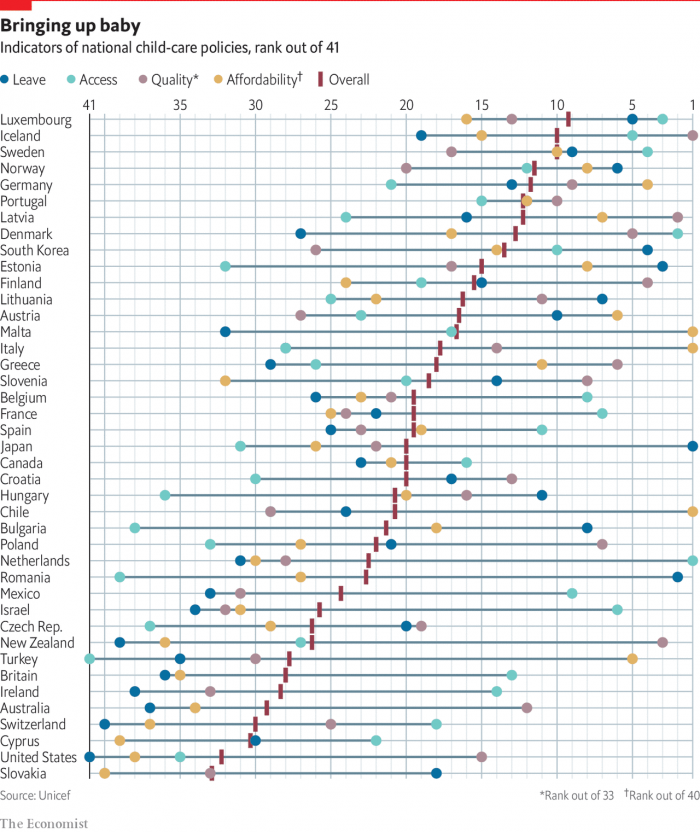

You guessed it. It’s not Switzerland. Tiny Luxembourg tops the table. Switzerland and the United States are among the meanest.

Source: The Economist, daily chart, July 1st 2021.

“WHEN A BABY arrives in the world, there is no reason it should be just the mother who takes care of it,” Emmanuel Macron, the French president, declared last year. “It is important to have greater equality in sharing responsibilities.” From July 1st, paid paternity leave in France will increase from 14 to 28 days. The first week will now be mandatory, with three days funded by the father’s employer and the rest by the state. It is expected to cost taxpayers €500m ($593m) a year.

Mr Macron is seeking to bring France’s child-care provision closer to that offered in European countries such as Norway, Portugal and Sweden. Using data from the OECD, a new report from Unicef, the UN’s children’s fund, reveals which countries give parents most support in looking after their children. It ranks 41 rich countries according to the amount of leave offered to new parents, the ease of access to education in early childhood, the quality of teaching and the affordability of child care. (The OECD’s leave data are from 2018, so do not reflect the new scheme in France.)

Luxembourg, Iceland and Sweden rank highest as they offer generous leave to both mothers and fathers and “combine affordability with quality of organised child care”, the report says. Luxembourg offers 20 weeks for mothers and two weeks for fathers on full pay, plus a further 34.6 weeks for both parents on two-thirds pay. The tiny, wealthy country also invests a lot in early-childhood education and care: in 2019 it spent an average of $11,400—more than twice the OECD average—on each child under five.

Slovakia, America, Cyprus, and Switzerland rank lowest, largely owing to the lack of time parents are permitted to take off after a baby is born and the cost of child care as they grow up. America is the stingiest of all 41 countries in the leave category: it is “the only rich country without nationwide, statutory, paid maternity leave, paternity leave or parental leave” the report observes.

Some countries do not offer fathers any time off work after the birth of a child. Even in countries where paternity leave is offered, it is generally a fraction of what is given to mothers. In the average OECD country, paid paternity leave is one-thirteenth that of paid maternity leave—1.4 weeks versus 18.1—meaning that the burden of child-rearing falls almost entirely on the mother.

But extending paternity leave would not necessarily lead to a more even sharing of the load. Even though they are entitled to less time off than mothers, fathers are less likely to take all that is on offer. Gender norms that position women as caretakers and men as breadwinners are not easily dismantled. Fathers often earn more than their partners, and so not taking full advantage of paternity leave can be a financial decision—especially if the leave is only partially paid.

Cheeringly, the take-up of paternity leave appears to change over time as cultural attitudes shift. In countries that have had paid paternity leave for a while, such as Sweden and Denmark (since 1980 and 1984 respectively), around three-quarters of men claim paid paternity leave. Other countries, such as France, take a firmer hand by stipulating a minimum period.

French fathers will now enjoy some of the most generous paternity leave of any country in the OECD. Yet they will still receive just a quarter of the leave granted to new mothers. The vast majority of citizens welcome the change, but many would like further progress. Boris Cyrulnik, a French neurologist who was appointed by Mr Macron to oversee a study of the first 1,000 days of a child’s life, recommended nine weeks of paternity leave. The child-rearing “equality between women and men” that Mr Macron hopes for is still gestating.