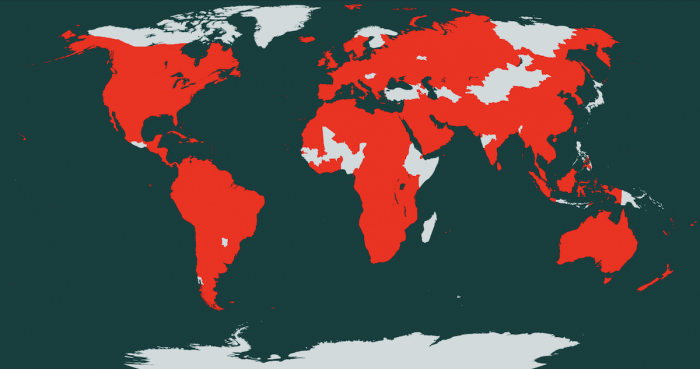

A map bouncing around social media shows “languages where the word for ‘mother/mom’ takes an m-sound”. It puts old maps of defunct empires to shame; scores of countries are shaded red.

There are two ways this near-universality might have come about. One is by spread. It is possible that language was invented only once, before the human exodus from Africa. This hypothesis—that there was once a “Proto-World” language—has led some researchers to scour distant languages in search of commonalities, which can then be used to try to reconstruct the parent words. But such work is rejected by most mainstream linguists. Human language is maybe 100,000 years old, possibly much older. Languages change vastly even in mere millennia. “Proto-World” proposals remain controversial at best.

There is another reason so many languages might have an m-sound in “mother”. Linguists generally argue for “the arbitrariness of the sign”: no connection exists between the word dog and the furry quadruped. A rare exception is onomatopoeia, where words representing the bark of a dog (bow-wow or Spanish’s guau-guau) vaguely resemble the sound. Yet most things are not subject to naming this way.

What about mama? It does not sound like a mother, but it does piggyback on another feature of language: the fact that some sounds are more widespread than others around the world. There are many dozens of observed consonants, from the clicks of some African languages to the “ejectives” (which make use of air pressure built up in the mouth) of Caucasian ones. These sounds are rare and hard for non-natives to learn.

In contrast, a few—such as b, m, p, t, d and k—show up far more frequently, in nearly every spoken language in the world. That is almost certainly because they are easy to make. A baby vocalising will, at first, make a vowel-like sound, usually something like “ah”, which requires little in the way of control over the mouth. If they briefly close their mouth and continue vocalising, air will come out of their nose, thus making the m-sound that is used in “mother” around the world.

Though the “mamas” bear the most obvious similarity, the “papas” have striking commonalities, too. Babies can easily stop their breath when they close their lips (rather than going on breathing through the nose). This produces a b- or a p-sound. It is surely for this reason that so many names for “father” use these consonants: papa in English, abb in Arabic and baba in Mandarin. T- and d-sounds are similarly basic, involving a simple tap of the tongue against the teeth: hence daddy, tatay (Tagalog) or tayta (Quechua).

Father and mother are, therefore, an oddity. F- is not especially easy to articulate; th-sounds are even harder. English, Greek and Spanish are unusual in having them, and French-, German- and Italian-speakers struggle mightily with them, often substituting related consonants. Even surrounded by English from birth, Anglophone babies master consonants in an order that roughly mirrors their frequency around the world. Children may struggle with th-sounds when they are five, or older still in many cases.

This helps solve the mystery of why, despite parents being formally known as “mother” and “father”, so few children call them that. (The same thing can be seen elsewhere, too: Russian for “father” is formally otyets, but children call their dads papa.) Few parents will insist on children using the proper term to refer to them, especially if it means waiting until a child is seven and can pronounce it.

Languages can violate these rules, though they do so within reason. Marathi has aai for “mother”, no doubt because vowels are especially easy for infants. And Georgian, like a few other languages, switches the expected labels: “mother” is deda and “father” is mama. No one uses a tongue-twister like, say, throlth.

Roman Jakobson, a Russian linguist, explained the final piece of the puzzle in the 1950s. Are babies consciously naming their parents the same way the world over? Probably not. They are cooing and babbling to practise the use of their vocal apparatus. It is the parents, desperate to communicate, who identify those early sounds as the baby’s “names” for them. (This may be why the names often feature two repeated syllables, to distinguish them from random sounds.)

It is hard to find linguistic universals amid the world’s dazzling variety. It is heartwarming to find a commonality embedded in another universal: the love that babies inspire in their mamas and their papas.

Source: we have found this article on economist.com.